Attorney General Jeff Sessions released policy directive 17-1 yesterday in which he announced a new Civil Asset Forfeiture program. What Sessions really did was reinstate the old Asset Forfeiture program that had been in place under AG Eric Holder. Allow me to explain.

Civil asset forfeiture – or civil seizure – occurs when law enforcement agencies seize property they suspect has been used in – or originates from – criminal activity. The item being seized is itself suspected of having been involved in a crime. It is literally a civil action against the property. Criminal charges against the owner of the property are not required – nor is an actual conviction.

In order to get the property back, the property owner must initiate a lawsuit, providing proof that the property was not used in – or acquired by – illegal means. Unlike a criminal trial, where “beyond a reasonable doubt” is the legal threshold – in a civil case, the “preponderance of evidence” standard applies. All the government need do is present enough evidence that makes the claim of illegality more likely than not.

Civil asset forfeiture is a Constitutional affront.

The old asset forfeiture program came to an end – of sorts – in January 2015, when then-Attorney General Eric Holder prohibited federal agency forfeiture – or “adoption” – of assets seized by state and local law enforcement agencies. Holder did so near the end of his term after coming under pressure from both sides of the congressional aisle.

Adoption occurs when a state or local law official (i.e. policeman) seizes property suspected of being involved in a crime and then transfers it to the federal government, which forfeits – seizes – the property under federal law. The local agency is then allowed to keep up to 80% of proceeds from the forfeited property. State laws are effectively bypassed in this process. Importantly, a criminal conviction is not required for this process to occur.

As an example, a vehicle is stopped in a state with strong property rights protection. The state policeman suspects drug dealing. Under that state’s law, the motorist can only have his property (cash, car) taken if he is convicted of a crime. However, by employing the use of Adoptive Procedure, the state police bypass the state’s property laws – and take the motorist’s property without convicting him of anything. The motorist does not even have to be charged with a crime. The property is turned over to federal prosecutors who forfeit the property under federal law. The state police are then allowed to keep up to 80% of the proceeds. The federal government keeps the rest.

The process of sharing in asset forfeiture proceeds is known as Equitable Sharing. The Justice Department has kindly provided the Guide to Equitable Sharing for State and Local Law Enforcement Agencies. There are two ways in which Equitable Sharing may occur. From the Guide:

Joint investigations are those in which federal agencies work with state or local law enforcement agencies or foreign countries to enforce federal criminal laws. Joint investigations may originate from participation on a federal task force or a formal task force comprised of state and local agencies or from state or local investigations that are developed into federal cases.

An adoption occurs when a state or local law enforcement agency seizes property and requests one of the federal seizing agencies to adopt the seizure and proceed with federal forfeiture. Federal agencies may adopt such seized property for forfeiture where the conduct giving rise to the seizure is in violation of federal law and where federal law provides for forfeiture.

Despite many reports, the Equitable Sharing program was never truly ended. Only the process of Adoption was prohibited. Specifically, “the Attorney General’s [Eric Holder’s] Order and related guidance do not preclude the federal forfeiture of property seized through joint task forces or as a result of federal/state investigations“.

Federal officials could still legally engage in asset forfeitures. State and local law officials could no longer do so on their own. But they could if they were participating with federal officials in some broad capacity.

The program of Equitable Sharing was briefly suspended in late 2015 due to budgetary issues but was then reinstated 3 1/2 months later by then-Attorney General Loretta Lynch. You can read more about it here, here and here.

AG Jeff Sessions is reinstating the ability of state and local law authorities to engage in asset forfeiture without participation in joint efforts with federal authorities.

Sessions is reinstating Adoption.

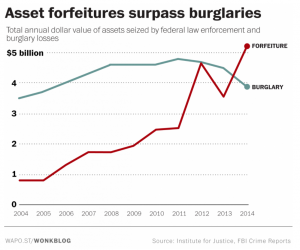

Here is a rather stunning graph by the Washington Post. It helps explain why Sessions – and law enforcement officials – want reinstatement of Adoption. The graph depicts the growth in federal asset seizures against the value of burglary losses:

Asset forfeitures were below $1 billion through 2005, rising to roughly $1.75 billion in 2008. Beginning with Eric Holder’s tenure as Attorney General, asset forfeitures exploded – from less than $2 billion to more than $5 billion in 2014. So much so, assets seized by federal authorities exceeded the value of items lost to burglaries by more than $1 billion.

The growth in asset forfeitures was the direct result of the use of Adoption. The process of Adoption became a significant funding source for state and local law enforcement agencies. These agencies became directly incentivized to engage in the process.

In March 2017, the Office of the Inspector General released a report titled, Review of the Department’s Oversight of Cash Seizure and Forfeiture Activities. The report opens with the following:

The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ, Department) has authority to seize property associated with violations of federal law and then assume title to that property through a process known as asset forfeiture. The Department views asset forfeiture as an important means of removing the proceeds of crime used to perpetuate and incentivize criminal activity and uses forfeited funds to both compensate victims of associated crimes and to fund certain Department and state and local law enforcement activities.

Over the past 10 years, forfeitures through the Department’s Asset Forfeiture Program have grown to over $28 billion.

As you read this, bear in mind the report focuses on activities after the restrictions AG Eric Holder was forced to put into place in January 2015. The issues highlighted are on an already restricted asset forfeiture program. As noted by the report:

The Attorney General’s 2015 Order and related guidance eliminates most opportunities for state and local law enforcement to use federal forfeiture to avail themselves of equitable sharing proceeds when federal involvement in a seizure is limited.

The report continues:

We found that the Department and its investigative components do not use aggregate data to evaluate fully and oversee their seizure operations, or to determine whether seizures benefit criminal investigations or the extent to which they may pose potential risks to civil liberties. The Department and its components can determine how often seizure and forfeiture advance or relate to criminal investigations only through a manual, case-by-case review of component case management systems.

Although the Department can aggregate data that can be used to identify associated risk factors and the outcomes of seizure activity, such as instances in which a portion or all of a seizure was returned to the owner as the result of a successful challenge, the Department’s investigative components do not actively use this type of aggregate data to evaluate and oversee seizure operations.

Specific findings:

We found that 85 of the 100 seizures occurred as a result of interdiction operations at transportation facilities, such as airports, parcel distribution centers, train stations, and bus terminals, or as a result of a highway interdiction or traffic stop. All but 6 of the 85 encounters or situations that led to interdiction seizures were initiated on the observations and immediate judgment of DEA agents and task force officers absent any preexisting intelligence of a specific drug crime.

The DEA could verify that only 44 of the 100 seizures, and only 29 of the 85 interdiction seizures, had (1) advanced or been related to ongoing investigations, (2) resulted in the initiation of new investigations, (3) led to arrests, or (4) led to prosecutions. When seizure and administrative forfeitures do not ultimately advance an investigation or prosecution, law enforcement creates the appearance, and risks the reality, that it is more interested in seizing and forfeiting cash than advancing an investigation or prosecution.

Our review revealed an area in which policy and training were inadequate for ensuring consistency in seizure operations. If seizure operations are not conducted consistently, this may foster a public perception that law enforcement officers are using their seizure authority in an arbitrary manner.

We also found that the Department’s investigative components do not require their state and local task force officers to receive training on federal asset seizure and forfeiture laws and component seizure policies prior to conducting federal seizures. As a result, state and local task force officers, who wield the same authorities to make seizures as the Department’s Special Agents, may not have received training on these topics beyond what is included in their respective law enforcement academy curriculum.

Methods of Seizure:

There are two primary methods by which federal law enforcement officers may legally seize assets: (1) an officer may request a seizure warrant from a federal judge if, prior to a seizure, the officer can establish that there is probable cause that an asset is subject to forfeiture or (2) an officer may seize assets pursuant to a lawful arrest or search, or when another exception to the Fourth Amendment warrant requirement applies and there is probable cause to believe that the property is subject to forfeiture.

During an encounter, the officer may either receive consent from an individual or determine that there is probable cause to search the individual and his or her personal effects without consent based on observations and/or questioning the individual. If, as a result of the questioning, search, or other investigatory action, the officer establishes probable cause that property has been used in the commission of a crime, the officer may seize the property.

There is an enormous amount of latitude contained within these provisions.

Conclusion of the report:

Asset seizure and forfeiture can provide considerable benefits to law enforcement. Seizure and forfeiture can financially undermine criminal organizations and deter illegal behavior by taking the profit incentive out of crime.

However, asset seizure and forfeiture also present unique potential risks to civil liberties. This is especially true for cash seizures made without a court-issued warrant that result in administrative forfeiture because law enforcement can seize and forfeit this fungible property without charging the owner with a crime and without any court involvement or review.

We found that the Department neither formally collects nor evaluates the data necessary to determine whether its seizures and forfeitures advance or relate to federal investigations…the Department and its investigative components cannot fully evaluate and oversee their seizure and forfeiture activities to ensure that they are used to advance investigations that help to dismantle criminal organizations and that they do not present a potential risk to civil liberties.

Most of these seizures occurred in interdiction settings, in which trained law enforcement officers make on-the-spot assessments of fast moving factual situations to initiate encounters that lead to seizure.

We determined that the DEA could verify that only 44 of the 100 seizures we sampled had advanced or were related to criminal investigations.

We identified instances, not addressed by DEA policy, in which task force officers had made different decisions in similar situations when deciding whether to seize all of the cash they had discovered.

The Department’s investigative components do not require their state and local task force officers to receive training on federal asset seizure and forfeiture laws and component seizure policies prior to conducting federal seizures.

The report closes by highlighting – in effect – the reasons why AG Sessions reinstated Adoption:

We also found that the Attorney General’s [AG Eric Holder’s] 2015 Order and related guidance eliminates most opportunities for state and local law enforcement to use federal forfeiture to avail themselves of equitable sharing proceeds when federal involvement in a seizure is limited. This is evidenced by a one-half reduction in the annual number of DEA cash seizures and a one-third reduction in the annual value of DEA cash seizures following the 2015 Order.

However, this policy and related guidance do not preclude the federal forfeiture of property seized through federal/state investigations or joint task force operations, such as joint transportation interdiction operations. This may be of particular concern because, as demonstrated in this report, these seizures may not always advance a federal criminal investigation or lead to a prosecution.

We also determined that the limitation on adoptions resulting from the Attorney General’s Order has financially affected state and local law enforcement, especially in at least two states where law enforcement frequently had used federal adoption because of restrictive state forfeiture laws.

I am all for enforcing criminal statutes and properly funding our law enforcement agencies, but this new order from AG Sessions is an affront to our Constitution and should be treated as such. If Sessions does not reverse himself, this is an issue the GOP-led Congress should swiftly address. Asset forfeiture as a direct result from certain types of criminal convictions is one thing. Due process has been fully engaged and ill-gotten gains disgorged as a result. Asset forfeiture without a criminal conviction – through a civil action – is an entirely different matter.

Civil asset forfeiture has always been Constitutionally questionable. To incentivize it through the practice of Equitable Sharing and Adoption is even more so.

newer post Media Ownership – Concentration, Control & Politics

older post Climate Change, CO2, an EPA Power Grab & Some Experts